Verb Phrases (Jurafsky Martin)

As presented in Jurafsky Martin Chapter 12: Constituency Grammars

See also Noun Phrases (Jurafsky Martin)

Verb Phrases consist of the verb itself and a number of other constituents. In simple structures these other constituents might be NPs or PPs and their combinations:

\(VP \rightarrow \; Verb\) eg. “disappear”

\(VP \rightarrow \; Verb \; NP\) eg. “prefer a morning flight”

\(VP \rightarrow \; Verb \; NP \; PP\) eg. “leave Boston in the morning”

\(VP \rightarrow \; Verb \; PP\) eg. “leaving on Thursday”

But they can be signifanctly more complicated. Entire embedded sentences can follow a verb. These are called sentential complements: “Tell me [how to get from the airport to downtown]"; “I think [I would like to take the other flight]".

We can express these with a furhter rule: \(VP \rightarrow \; Verb \; S\)

Likewise another potential constituent for a VP is another VP, common for verbs like want, would like, try, intend, need: “I want [to fly from London to Paris]"; “I tried [to arrange my flight]".

One complexity is that not every verb is compatible with every type of verb phrase. For example want is compatible with a NP complement or an infinitive VP complement: “I want a flight…", “I want to fly to…". find by contrast only works in the former “She found a flight”, but not “She found to fly to Dallas” (query though what about “why didn’t she take the train?", “She found to fly was cheaper”).

All grammars therefore subcategorize verbs to reflect these differences.

Traditional ones distinguish transitive verbs: those that take a direct object NP (eg “I found a flight”) from intransitive verbs that do not (like disappear, go). More modern grammars might have as many as 100 subcategories.

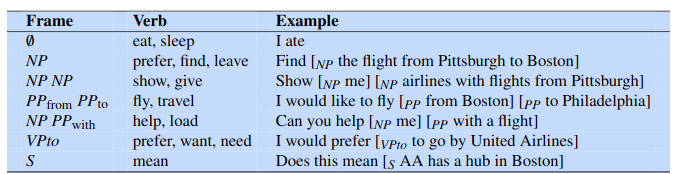

We can think in terms of the concept of a subcategorization frame for a verb.

We say that a verb like find subcategorizes for a NP. While a verb like want subcategorizes for either a NP or a none-finite VP.

These constituents that the verb subcategorizes for are called their complements. The sets of complements for a verb are its subcategorization frames.

Shown with the following table in the book:

Alternatively we can think in terms of logical calculus. The verb is a logical predicate, and the constituents are the logical arguments of the predicate. So we end up with logical relations like

FIND(I,A FLIGHT)orWANT(I, TO FLY).We can capture this association of verbs and their complements by subtyping the class Verb and modifying our production rules. The downside is it massively increases the number of rules.