CM3035 Topic 09: Deploying a Website

Main Info

Title: Deploying a Website

Teachers: Daniel Buchan

Semester Taken: April 2022

Parent Module: cm3035: Advanced Web Development

Description

Deployment for production.

Key Reading

Continuous Integration Tools

Automated Deployment Tools

Other Reading

Lecture Summaries

9.1 Introduction to Production Deployment

Deploying a website is a special case of the more general process of deploying applications.

Deployment itself is the activities needed to make software available to users. This includes releases/versioning, installation, and updates.

A critical concept in real-world engineering is the concept of an environment, the processes and hardware that are used for a particular purpose.

So the development environment is the hardware and processes used to develop the application before user access.

The production environment is the hardware and processes where the software is made accessible and operational for users.

These environments are associated with different roles:

| Development Roles | Production Roles |

|---|---|

| —————– | —————- |

| Software development | Release management |

| Programming | DevOps |

| Project Management | Systems administration |

| Build management/engineering | Database administration |

| Release management |

When you deploy applications you need to consider the resources you need - RAM, cores/threads, machines, bandwidth, redundancy.

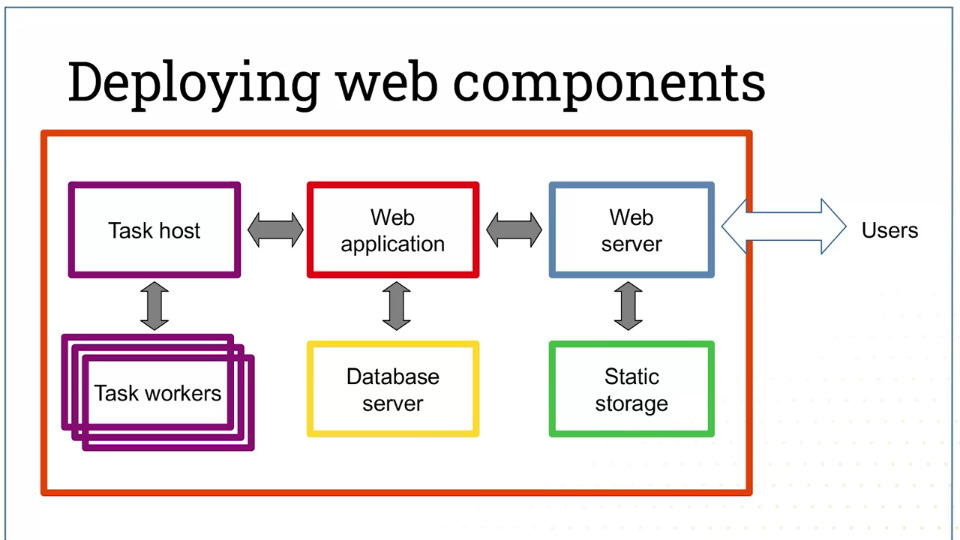

We can separate out the components of complex systems onto different machines to separate concerns and spread the resource requirements:

The complexity then becomes managing the infrastructure, all the components are in sync and communicating correctly.

Dev-Staging-Production model

It’s common to work on a dev-stage-prod model where we have different environments for different purposes.

Development environments might involve a single computer, running all components locally, one per developer, with development settings, non-secure.

Staging environments replicate more closely the production environment, ideally an exact replica. This tests that it works as deployed. It can be used for User Acceptance Testing.

You might have a qa environment for stress-testing.

The production environment is the final deployment hardware, user accessible and everything needs to work.

WSGI and ASGI

When working with Python web frameworks they all adhere to one or both of the WSGI or ASGI communication standards, so you need to be aware of them.

Web Server Gateway Interface (WSGI)

An interface specification, defines how the different elements of a web application communicate with each other. EG how a server like Apache can communicate with a web application like Django/Flask etc.

It’s implemented in Django by default.

If using Apache as a web server, you can implement wsgi with the mod_wsgi Apache module.

If using Nginx you can implement with the uWSGI extension.

Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface (ASGI)

Successor to WSGI, supports async applications (needed for websockets)

Standard provides ASGI-WSGI adaptor so your async application can call synchronous components.

In Django this is provided by the django-channels package.

No support natively in Apache/Nginx. You’ll need a different server like Daphne, or Uvicorn.

9.108 Packaging a Web app

So we’ve finished our web app and are ready to package it for deployment. How do we do that?

We’ll need to tell the environment what packages and dependencies are needed to run the application.

We can do that in Python land with pip freeze > requirements.txt

Then we can zip or tar to create a package, like tar -zcvf bioweb.tar.gz bioweb/*

9.110 Configuring a Web Server (Apache)

Now we want to install the app on the production hardware.

The first thing is to install a production web server, Apache or NGINX.

For example to use Apache we might say sudo apt install apache2 libapache2-mod-wsgi-py3

We will often want to use a virtual environment to isolate our application from its environment.

Cloud providers will often have services pre-installed, like Apache/NGINX, and firewalls set up.

It’s a good idea to remove packages you don’t need.

You can collect static assets and serve them separately so the web server can serve them more efficiently. you can specify in django settings a STATIC_URL and STATIC_ROOT (like os.path.join(BASE_DIR, "static")), then run python manage.py collectstatic to collect all the static assets in your project and place them in the static directory.

now we can configure Apache.

check in /etc/apache2 for the various configs. If you check ports.conf you can check the port, but default is usual.

If you look in /etc/apache2/sites_available/ you’ll see 000-default.conf which is the default configuration.

we can then add in the configuration for our application:

<VirtualHost *:80>

....

# This interacts with the collect static command to set the path to the static folder

Alias /static /route/to/static/assets

<Directory /route/to/static/assets>

Require all granted

</Directory>

<Directory /route/to/main/wsgi/config>

<Files wsgi.py>

Require all granted

</Files>

</Directory>

WSGIDaemonProcess myapp python-path=/path/to/my/app python-home=/path/to/python/install/venv

WSGIProcessGroup myapp

WSGIScriptAlias / /path/to/my/wsgi.py

</VirtualHost>

Then start/restart the server with service apache2 restart

9.112 Database Servers

We’ve been writing applications backed by the postgres database, but we’ve just used the default config.

It’s rare that you need to tune postgres. The application user should have only the required permissions, the main db user should be unique, not root.

If you go to /etc/postgresql you’ll see a directory for each version of postgres. If you go to /etc/postgresql/version/main/postgreql.conf you’ll see the huge file with lots of controls. A large number are commented out.

One critical setting is listen_address, which IP address to listen on. Defaults to localhost only, ie only to connections on the same machine. In a prod install you’ll have the db on another machine, and set the IP addresses of any connecting machines.

max_connections is also important. It sets the maximum number of connections. If you’re running multiple web apps, each attaching to the db, you may need to change this.

shared_buffers is the size in memory of caches and queries. You might need to increase this, depending on the OS and its kernel you might need to change the setting in the kernel to allow the db to use more memory.

work_mem is the space available for large computations, like sorting. You might need to increase this if your db has expensive computation to do.

effective_cache_size might need the disk cache if you run out of RAM and need to fail over. If you find you’re using the disk cache you probably need to look at redesigning them anyway.

error reporting and logging this section shows where issues are logged.

9.2 Deploying Django

9.201 Django Settings

Things that are worth looking at:

BASE_DIR this is the base directory, and can be referenced in the app when you need to know the application’s location (eg for relative paths).

SECRET_KEY this is a random ASCII string used across the application for when a random string is used. Must be kept secret. Generate a new key for each machine.

DEBUG set to false for production.

ALLOWED_HOSTS list of domains that are allowed to make requests to your application.

INSTALLED_APPS our apps and all the apps we rely on (like sessions, auth)

MIDDLEWARE all the layers that handle auth between request and response

DATABASES the db settings.

STATIC_URL the url we use to link to static assets

STATIC_ROOT the path that the web server needs to know to serve static assets efficiently.

9.203 Logging

We can easily install a logger using Python’s default logging mechanism.

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def my_func():

logger.warning('something has happened')

The classes of logging message are debug, info, warning, error, critical.

Now if we look at the settings we can do this:

LOGGING={

'version': 1,

'disable_existing_loggers': False,

'handlers': {

'file': {

'level': 'DEBUG',

'class': 'logging.FileHandler',

'filename': '/var/log/django.log'

},

'loggers': {

'django': {

'handlers: ['file'],

'level': os.getenv('DJANGO_LOG_LEVEL', 'INFO'),

'propagate': True,

},

},

}

9.205 DNS

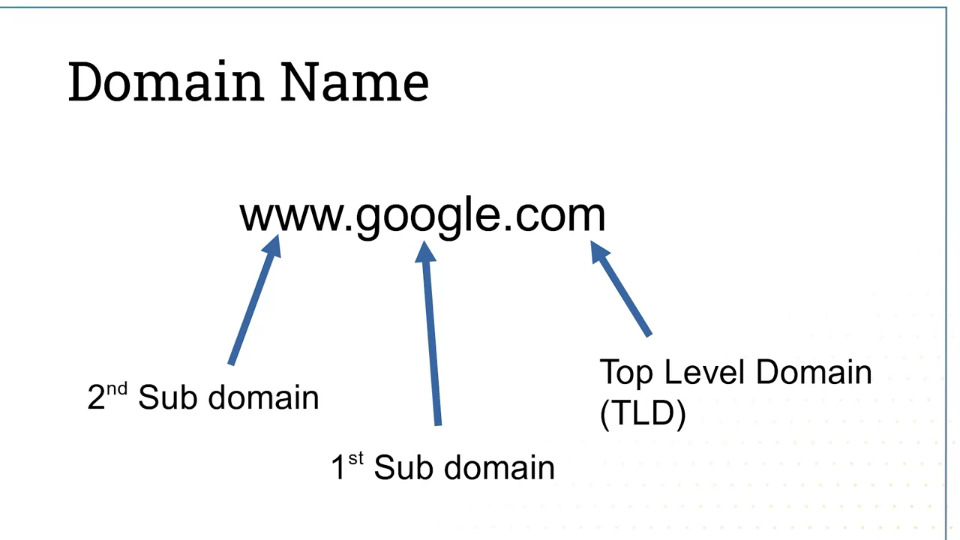

Once we have our server running and it’s connected to the internet it will have an IP address. Usually though we don’t use IP addresses directly, we use domain names.

The Domain Name System, or DNS provides human-readable names to proxy for IP addresses.

ARPANET used to distribute a centralised HOST.TXT file which mapped host names with IP addresses.

But this was clearly not scalable. So the original spec for DNS was floated in 1983, and implemented in 1984 (updated in 1987).

The implementation is a hierarchical system called the domain name space, and set of name servers holding a database of domain name-IP mappings.

The hierachy is as follows:

You can have as many subdomains as you like, but by convention we use www as the default subdomain for web pages.

If you choose a domain you need to register it.

This is managed by ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). They farm out TLDs to other companies.

eg .co.uk is run by JaNET; .edu by EduCause; .com by Verisign; .biz by Neustar etc.

These companies are responsible for assigning subdomains within their TLD. But you don’t register directly with them, you go via a third-party registrar company.

9.3 Deploying Django

Deployment Preparation

Arrange hosting

Register DNS

Set up staging and production environments

Install software

Go live!

Hosting:

Three scenarios

There is no hardware in place: Purchase/hire servers

Hardware is already in place: reinstall as needed

Moving servers: reinstall as needed; rewrite existing DNS

Register DNS:

- Determine type of TLD. In some cases we apply direct to the registrar, but mostly we apply via a third party.

Set up environments:

Install staging environment

Install production environment

Ensure all passwords, credentials, and secrets are different

Install software:

Copy/uplaod application to server(s)

Separate out production and staging settings

Ensure creds etc are different.

Setup environments:

In django there’s a settings file. Better to change this to a settings folder. within that you might have a base.py for all common settings, and then an environment.py file for each environment with the environment specific settings.

For passwords/secrets, make sure these are NOT in the settings files themselves. They should be in an ENV variable at runtime, or provide a file of secrets (or set them up in your hosting provider).

Go live:

With DNS in place start your server (NGINX or whatever).

Releasing an Application

Common for projects to have a release schedule.

A release is a fixed version of the application that is fully functional with a defined set of capabilities.

Development now we’ll have a shared code repository. We’ll have a list of functions that the software is designed to have and bug fixes we’ve needed to make. Then we use a ‘fix version’ to mark a release with a version number.

Typically in the major.minor.patch version semantics.

Major signals breaking changes usually. Minor usually indicates functionally improvements that are not breaking. Patch indicates minor bug fixes etc.

We might copy the application codebase or clone a repository. Then we configure it for the upgrade. And restart the server.

Deployment Targets

Usually we have some deployment target in mind:

local computer or server (for small org)

Server in the data centre (for large org with specific infra)

Server in the cloud (increasingly common)

Local servers are self-managed, physical access, manage own dev ops, manage own sysadmin.

Managed servers:

Systems admin is provided

No physical access

May manage own devops

Buy all hardware up front

Cloud computing:

Third party provider

Sysadmin provided

No physical access

Manage own devops

Ongoing rental costs

Storage/bandwidth costs

flexible scaling

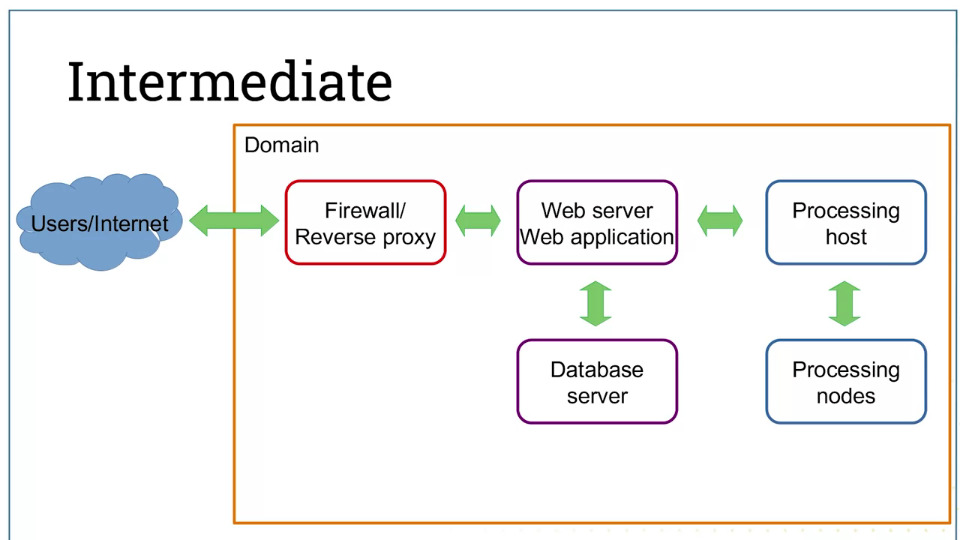

9.307 Deployment configurations

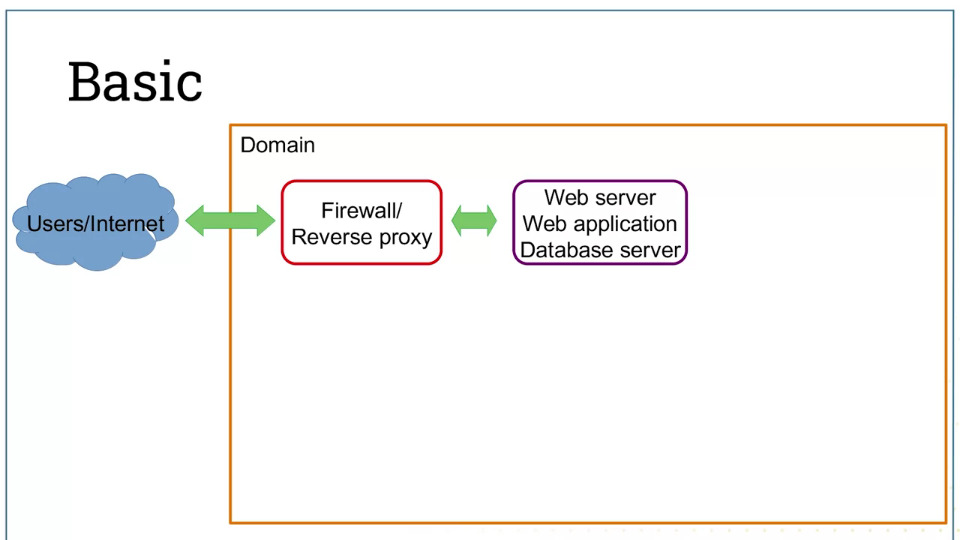

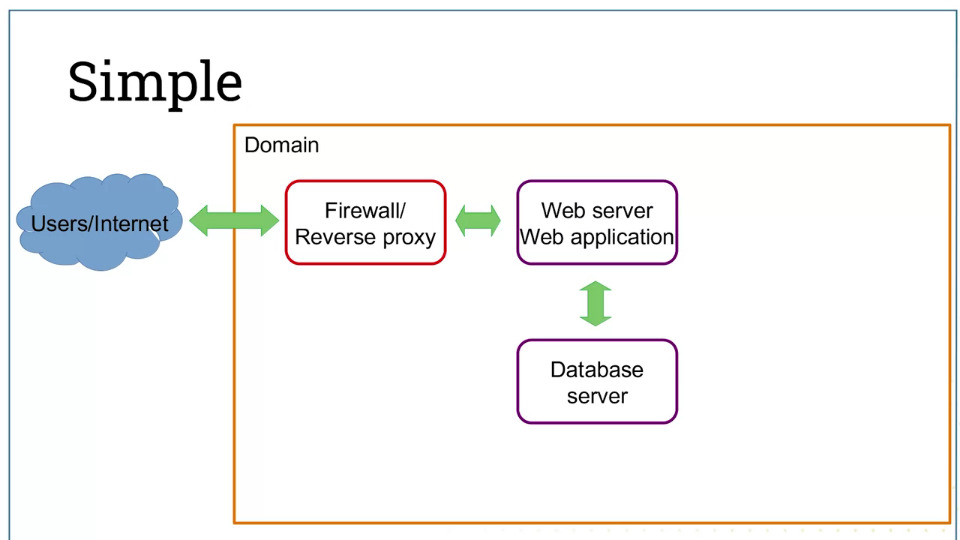

Configuration is endless in possibility but there are some basic patterns:

One step up is moving the database on to another machine:

Small bit of latency as the app and db now communicate over the network.

One step up again is:

Here we have some kind of queue system, eg an email processing system, and the host then communicates with processing nodes.

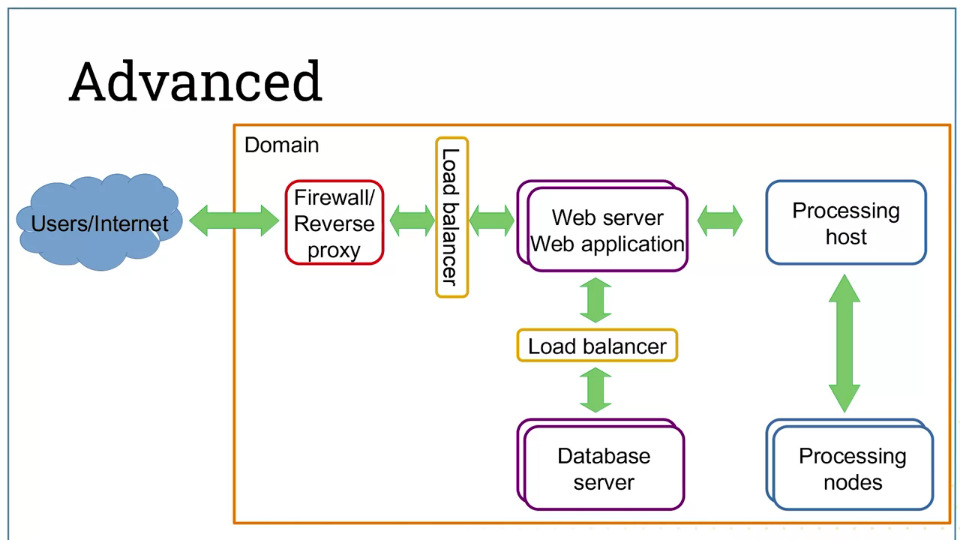

Finally more advanced setups might need some redundancy:

Now we have new concerns - synched databases, load balancing etc, which we cover next topic.

9.4 Deployment Automation

9.401 Sysadmin and devops

When deploying apps there are two overlapping roles - systems admin and devops.

Systems administration is the management of computer hardware - installing hardware, config, user access and control, updates, virtual machines, networking…

DevOps, involves managing the installation and deployment of applications: Build tools (CI tools), testing, packing, releasing applications, configuring applications, monitoring application performance.

9.403 Continuous Integration

A development practice that we’re developing code to a minimum quality standard that could set us up for automated deployment.

It’s the practice of regularly merging developers’ code to the central repository, several times a day, to ensure that the centrally stored code is functioning.

The workflow would look like:

Develope code unit

Pass local/developer tests

Merge code to central repository

Pass repository test

Deploy code to staging

Tools that are used to manage these Continuous Integration processes include:

9.405 Deployment Automation

If we need to repeat installation processes in a reliable way we can’t do it by hand.

If we’re setting up an application over many machines, it’s impossible.

So there are several deployment automation tools that we can look to: